I found this week’s reading very interesting because they, like many parts of this class thus far, made me analyze aspects of artistic and everyday visual perception in a way that I was not accustomed to, and allowed me to see and conceive of many things I hadn’t considered. For this reason I particularly like the two Solso chapters, and I consistently found myself amazed at the distinctions he brought up and the way they were illustrated.

In chapter 7, he outlines the ways that we analyze the space between objects through monocular depth cues. He describes how our assessment of relative size is affected by both size of the image that is seen (bottom-up processing) and knowledge of the object (top-down processing), and how occluded objects tend to appear as complete but layered shapes. I found his examples of shadow particularly riveting; not only does the addition of darkness and highlights create the illusion of depth in a two-dimensional image, but that concavity and convexity can be reversed with the simple reversal of those shadows (by turning the picture upside down, for example). He includes orientation, elevation within the frame, linear perspective, and texture gradients, and makes very interesting claims about how color influences depth perception in relation to atmospheric depth (where colors and shapes become more blurry, pale, and blue as they recede) and the fact that warm colors simply advance to the foreground over cool colors. The church in Milan was a particularly fascinating example of these tools at work (I had to stare at the photograph for several minutes before I could convince myself that it was not in fact three-dimensional).

I ran into trouble with these depth cues, however, in Arnheim, when he claims that the United States map provides unreal depth effects that must be avoided: “...we see that a corner of Wyoming lies on top of a corner of Utah, and that a corner of Colorado lies on top of Nebraska. No knowledge that this is not so prevents us from seeing what we see” (p. 248). As I read this section, I was perplexed, as I didn’t think I had ever experienced the illusion before; of course when I looked at a map I immediately saw it this way, having just read the chapter (for the life of me I cannot now remember if I ever saw the states as overlapping now). What interested me beyond this point, however, as I was looking at the map more thoroughly, was how states like Pennsylvania, New Mexico, Missouri, Mississippi, Montana, Florida, etc. did not provide this illusion to the same extent, unless I tried very hard to make it happen. Firstly, I hypothesized that our general schema of maps (see next paragraph) presupposes that states/countries border each other rather than overlapping, and that they are not perfect, simple shapes. When the states do remind us of more simple shapes (e.g. the rectangle-shaped states of the West), the overlapping illusion is easier to sustain, or for Arnheim, impossible to escape.

Part of this is of course related to chapter 8 in Solso, where he explicates prototypes and how they influence how we think things should appear as opposed to how they do appear. Solso explains that certain schemata, derived from our experiences with the world, are activated when we participate in certain activities, telling us what to expect. In this way, Solso argues, and I am quite inclined to agree, that though all viewers perceive a visual stimulus in the same way (i.e. light is reflected off of it, which falls on the retinas, and signals are sent to the brain), this stimulus will activate different schemata that will result in the stimulus being experienced in a different way. In other words, the semantic value or “meaning” of the stimulus will change.

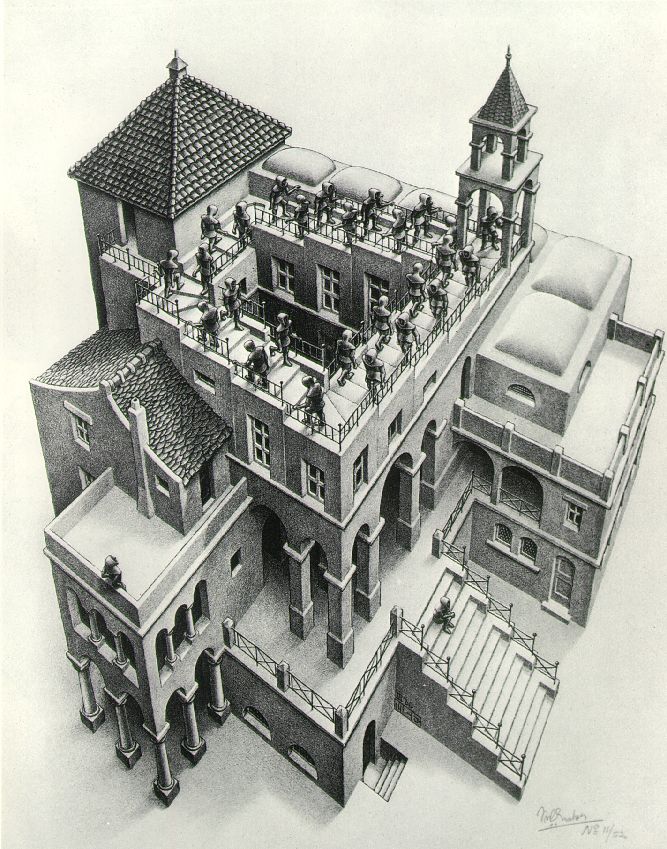

These schemata become abstracted into prototypes, Solso says, which in turn can influence our conceptualization of art and perception of individual art objects. Particularly, art often serves to violate these prototypes resulting in visual dissonance and psychological tension. In some ways, Solso seems to claim that this is in fact the purpose of much of art, “to demand active participation [from the viewer] in the construction of ‘reality’” (p. 237).

Finally, Solso also revisits the question of artists and scientists, brought up somewhat facetiously in the Wade article (I think?) from a few weeks ago. Solso, however, puts artists and scientists in the same camp, seeking out aspects of perception that excite viewers in some way. He says artists “do not invent art” in the same way that scientists do not invent science: “As scientists discover the laws of the universe that are congruent with mind, artists discover visual images of the world that are harmonious with mind” (p. 257). Of course, “harmonious” can have many different meanings, and I don’t think Solso intends to exclude visual dissonance. In fact, I think he means that dissonant with expectation or not, art (or perhaps “successful” art, just like successful theories) accords with the mind in such a way that it merges with the mind of the viewer and provokes thought.