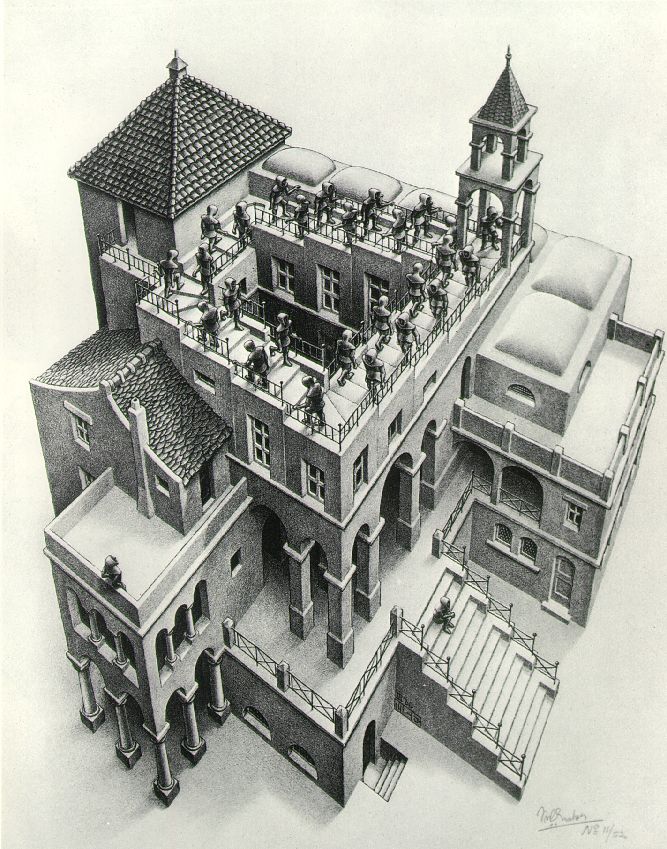

First, I thought Solso described the process of making canonical images, and our dependence on/propensity towards storing prototypical images in an illuminating way--articularly as relates to viewing art. We've talked before in class about how each of us, after organizing the visual information, applies his or her own personal experience and knowledge to the work. Solso described how artists can work within schemata, or play against our expectations, creating tensions that can make art disturbing, thought provoking, and memorable. Here I thought of Escher--linking, actually, the ideas of those tensions and the earlier chapter on perspective. Escher creates images that both confirm and deny our expectations of the visual world--he tricks us into thinking the stairs in this piece are continuous. They appear one way, manifested in two dimensions on the page, but our logical experience resists the visual evidence, giving us that eerie gap between what's real, what's possible, and what we're seeing.

I also appreciated Solso's description of how we create larger schemata that encompass, say, baroque art, or impressionist art, or Christ figures. I had an odd experience last fall--when traveling in Paris, I went to the Louvre and saw the painting below. Before looking at the title (or, rather, the translated title card, since I don't read French), I was bemused as to the subject. I thought, "This must be a Madonna and Child painting, because of the colors and the attitudes of the figures and the time at which it was painted...", and yet another part of me resisted this interpretation because I had never seen a painting in which Mary was nursing and had a breast exposed. It didn't fit with my Madonna/Child schemata. Yet, of course, this is a representation of Mary and child, and once I had registered that within my consciousness, suddenly in every museum I went to I found a painting of Mary nursing. Because I'd never noticed it before, the idea of a bare-breasted Madonna was not part of my experience of art--but once I had seen one example, I was able to incorporate many more images into my schemata.

Did anyone else do the depth perception tricks? I happened to be holding a mechanical pencil when I read that passage, and it was quite hard to insert the lead with one eye closed. However, the other little trick--trying to connect your index fingers--was quite easy. I later tried a needle and thread and experienced the same trouble as with a pencil. Then it came to me that obviously I'd be able to touch my fingers together without visual cues, because I can do it with my eyes closed, based on my kinesthetic awareness of my own body. This led me to question our reliance on visual cues for certain tasks--or rather, to wish to know more about the interdependence of visual cues and kinesthetic cues. For example, I'm not an extremely experienced knitter, but I have been knitting for years, and can make quite complicated things. Yet I can't knit without looking at the work, even though so much of it is based on fine motor control memory. Surely if I can type without looking at my fingers, I should be able to knit. Is my inability to do so caused by a false reliance on visual cues? In other words, if I turned out the lights and tried to knit would I find that it was easy, based simply on the sense of touch? Are we blind (forgive the pun) to certain over-reliance on sight?

A third personal connection I made to the readings--Livingstone talked about various methods artists employ to "flatten" their visual scene, in order to render it two-dimensionally. I spent a lot of time seeing if I could do the same thing, lose my sense for the depth of my visual field--and then I realized I already had my own method for this. Its aim is different, however. I'm a stage manager, and when calling cues during a show it's often necessary to be able to see the entire stage at once--if, say, you have a sound cue based on one actor's movements and a light cue based on an actor on the other side of the stage. To acheive a full-stage focus you have to relax your gaze and let it hover a little above everything--I find that this makes it seem as though I'm watching a flat picture, like on a television. I do this so I can see everything, not specifically to lose depth perception, but it's interesting that it has the same effect. I've also noticed that it makes movement much more noticeable. I wonder if this is because my brain is trying to latch onto depth cues--as Livingstone and Solso both explained, relative movement is one of our primary ways of perceiving depth--just as I'm consciously trying to remove them.

Tina you draw some really interesting connections between your own experiences and the reading. I agree with you that trying to make one's fingertips meet is very easy because of body awareness. Your knitting question is a good one, I also am an experienced knitter and find it very difficult to confidently knit without looking, I can do it but I worry that I am making mistakes. I think you are right, we depend on our visual sense more than we really need to. I think it becomes our dominant sense because we let it be.

ReplyDeleteI also enjoyed your discussion of schemata. I think this was a very interesting part of the Solso reading because it was so simple but insightful. When one goes into a museum expecting to see abstract art there are certain assumptions, and expectations that one brings to the artwork. People approach different styles of paintings and artwork with unique expectations. I think it is interesting when you see something that you were not expecting to see. If you go to an exhibit expecting it to be in a certain style and it is not for a while you still try to view the artwork though the lens of that presumed style, then you revert to another schema. How many times have I heard someone reply when asked whether they enjoyed a movie, a play or an exhibit, "well it wasn't what I expected." Seeing something unexpected can be uncomfortable, hard to accept, and therefore not necessarily pleasurable. I guess it's all about perspective and schema.

I think that Tina really provides an interesting discussion of expectation and archetype, especially in her discussion of the Madonna and Child motif that we so often see in the art from around the centuries.

ReplyDeleteI'm now a dance third this semester. Previously, when watching modern and post-modern dance, I felt I couldnt' connect to it -- the dancers and practitioners must be engaging the practices with some knowledge that was high above my head. But after taking dance history, composition and fundamentals, I'm able to have a more accurate take on the pulse of the watch I'm seeing: artists questioning retrograding or playing with principles of time and space in interesting ways. It's interesting how our mind gets builds schematic muscles and the expectation that comes with that.